Rigorous CLP training program spans disciplines to help graduate students launch careers — in the lab and beyond

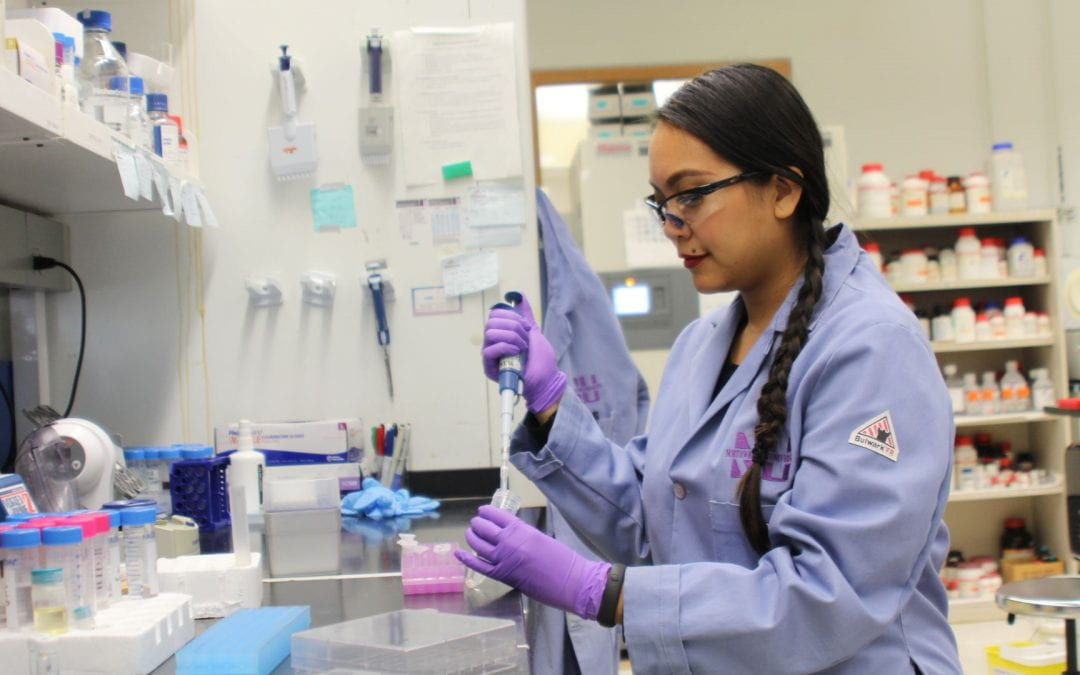

As a biologist in the lab of chemist Chad Mirkin, Jennifer Ferrer has learned the value of being “multilingual.”

“When I arrived four years ago, I realized there weren’t many people with biology backgrounds,” says Ferrer, a PhD student enrolled in Northwestern’s Interdisciplinary Biological Sciences Graduate Program (IBiS) and a trainee in the Chemistry of Life Processes Predoctoral Training Program. “I quickly learned that my ability to discuss biological systems in a relatable way could help guide how some of the more chemistry, materials science, and engineering-focused students think about designing nanomaterials for bio applications.”

That aspiration is a hallmark of Northwestern’s National Institute for General Medical Sciences (NIGMS)-sponsored Chemistry-Biology Interface training grant, launched in 2013. Open to rising second-year students in five graduate programs — chemistry, biomedical engineering, chemical and biological engineering, the Driskill Graduate Program in Life Sciences, and IBiS — the NIH-funded Chemistry of Life Processes Institute (CLP) curriculum requires students to integrate biology and chemistry through coursework, lab training, and student engagement.

Professor Richard Silverman, director of the Chemistry-Biology Interface Predoctoral Training Grant Program at Northwestern

“Graduate education, in general, is often focused on individual projects, and the student is somewhat limited in his or her training experience,” says Richard Silverman, Chemistry-Biology Interface Predoctoral Training Grant Program director and the chemist who synthesized the small organic molecule now marketed by Pfizer Inc. under the name Lyrica. “This program requires each trainee to select two faculty mentors from two different areas of expertise and to carry out research in both laboratories.”

Ferrer’s secondary mentor is Jason Wertheim, the Edward G. Elcock Professor of Surgical Research and a transplant surgeon at Northwestern Medicine. Both Mirkin and Wertheim hold faculty appointments in multiple schools, a common attribute of CLP preceptors. Of the program’s 49 affiliated faculty, nearly half hold multiple appointments, spanning 11 departments within the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, McCormick School of Engineering, and Feinberg School of Medicine.

“The CLP Training Program is at the heart of the Institute’s mission of training the next wave of scientific leaders, particularly ones who fearlessly innovate and invent regardless of disciplinary boundaries to create the therapeutics and diagnostics of tomorrow,” says Tom O’Halloran, founding director of the CLP Institute and the Morrison Professor of Chemistry.

The program’s secondary mentors are meant to provide complementary training that will be essential for the successful completion of graduate research taking place in the primary mentor’s lab.

The focus of Ferrer’s study has been to develop and test a novel nanoparticle-based therapeutic (Mirkin lab) that can weaken inflammation and the immune response in the context of surgery, specifically liver transplantation (Wertheim lab).

Professor Neil Kelleher, associate director of the Predoctoral Training Grant Program at Northwestern

“The trainees emerge with a more well-rounded view of the interface between chemistry and biology,” says Neil Kelleher, chemistry, molecular biosciences, medicine and Predoctoral Training Grant Program associate director. “The NIGMS training grant allows a student’s graduate career to complement the depth of traditional doctoral training programs with a unique breadth of cross-disciplinary training.”

This is reinforced through their completion of courses like Chem/IBiS 416, “Practical Training in Chemical Biology Methods and Experimental Design,” which provides hands-on experience with instruments and methods in a range of analytical, imaging, and life sciences core facilities. The course was specifically designed by Kelleher in 2015 to meet the program’s goals for providing experiential training by leveraging the expertise of PhD level staff in Chemistry of Life Processes Institute core facilities.

In addition to CLP-hosted seminars that explore science-related career options outside of research — like patent law, consulting, journalism, and entrepreneurship — trainees invite several distinguished speakers to campus each year and act as their hosts. Trainees also have an opportunity to interact with CLP Institute Executive Advisory Board members, who are leaders in the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and other industries.

“The student-hosted seminars are one of the best components of the CLP program,” says Rick Betori a third-year graduate student doing his primary research in the lab of Karl Scheidt, chemistry. “These seminars give us an amazing opportunity to interact with speakers and talk with them about their labs, their views on science and the scientific landscape, and really get insight into new cutting-edge areas of scientific research.”

Rick Betori, left, and Professor Karl Scheidt, chemistry. Betori is a third-year graduate student conducting his primary research in the Scheidt Lab.

Betori’s research is focused on the development of small-molecule chemical tools to study the protein telomerase, a molecule implicated nearly universally in cancer. Betori recalls sitting down with Scheidt in 2016 to discuss the research direction Betori wanted to take.

“This was the first time in my professional career that I was expected to generate my own research project and we talked for more than two hours,” says Betori. “I remember leaving that conversation feeling empowered to go do the science and pursue ideas and projects that I thought were truly interesting, all the while knowing that my adviser would be there to provide guidance and training along the way.”

Betori spent the summer working in the laboratory of his secondary mentor, Stephen Kron, molecular genetics and cell biology at the University of Chicago, learning and applying biological approaches to studying the metabolism and stability of his compounds in cancer models. Betori’s research has already led to a first author publication on chemical synthesis of new tools for targeting telomeres. The cross-institutional mentorship was born out of an existing collaboration between Kron and Scheidt.

In the lab, CLP trainees also become mentors in their own right, helping Lambert Fellows — a program designed to provide multi-year funding for hands-on laboratory research to rising sophomores and juniors — pursue careers in research. In total, the CLP graduate program has awarded 28 National Institutes of Health predoctoral training appointments and 10 University fellowships over the past five years. The highly successful program has resulted in trainees obtaining multiple National Institutes of Health predoctoral fellowships, two American Chemical Society predoctoral fellowships, and one Howard Hughes Medical Institute Gilliam Fellowship. CLP trainees have gone on to become postdoctoral fellows at the Scripps Institute, senior scientists at Abbvie and Merck, patent experts, and one is preparing to enter law school.

“Although there are many similar training programs throughout the country, I believe this program is unique in its emphasis on collaboration and interdisciplinarity and on the varied experiences trainees have that will help shape their careers,” says Silverman.

One recurring theme in talking to trainees is their sense of belonging.

“For me, it’s the human component that stands out,” says Ferrer. “I feel there’s such a sense of community, inclusion. That feeling definitely stems from the wonderfully supportive CLP leaders and administrators who manage the program and constantly ask trainees for their input on how to grow it and make it an even more rewarding experience.”

The CLP Institute was created to empower a new paradigm of scientific discovery that converges and integrates the current molecular approach with another layer of information that describes the impact of chemical and physical forces on the shape of molecules and their interactions. Institute faculty are renowned leaders in nanoscale imaging, top-down proteomics, theranostics, epigenetics, computational modeling, and inorganic physiology.

CLP is one of more than 50-plus Northwestern University Research Centers and Institutes (URIC), cross-disciplinary knowledge hubs designed to bring together talent from across the University’s schools. The Office for Research provides business and administrative support for the URICs.

Article originally posted on Northwestern Research News. Written by Roger Anderson